The Wing Family: Seduction Scandal in Meldreth in 1820

Introduction

We first stumbled across this story online when we found a copy of the Annual Register, which gave the case as Gwynne v. Jenkins. Although we were not familiar with the Gwynne family, we had no reason to doubt the accuracy of the report until Trevor Hamilton, a descendant of Susannah Sophia Wing, added a comment to this page in August 2012 (see below). Further research showed that the case was actually Wing v. Jenkins. Evidence from parish registers and several newspaper reports of the case have been found to support this. Several names have been changed in some of the original reports, possibly in an attempt to protect the identity of those involved. There is another page on this site, giving more information on the family history of the Wing family.

The following account is based on the report printed in The Annual Register compiled by Edmund Burke and published in 1823, although we have now substituted Wing for Gwynne. The original document can be seen by clicking on the link at the bottom of this page.

Although it has not been possible to identify with certainty the public house referred to in the text, we believe it is likely that it is the Green Man in North End. Members of the Wing family held the licence both for this pub and the Bell, but the Green Man is about half a mile from the Course residence, as described in one of the newspaper reports.

Court of Common Pleas — Seduction

Wing vs Jenkins. This was an action to recover damages from the defendant, Augusta Paul Jenkins, a ‘medical man’, for the seduction of the plaintiff’s daughter, Susannah Sophia Wing.

Sergeant Lens, for the prosecution, stated that Mrs Wing had been left a widow with three daughters and a son, and ran a small public house, in Meldreth, about 10 miles from Cambridge. This business, however, was inadequate for their support and so Mrs Wing found it necessary to move to Cambridge to find work leaving her family and the public house under the management of her father and mother-in law during her absence. Susannah Sophia Wing, the eldest daughter, was then just 16 years of age. Jenkins, the defendant, was a medical man of about 30 years of age who professionally attended the family. It was at Meldreth, in the absence of Mrs Wing, that he broke the confidence reposed in him and took advantage of the weakness of the child. This intercourse took place in 1820 and the unfortunate young woman was delivered of a child in the following year.

The learned Sergeant was proceeding to read a letter from the defendant addressed to the daughter, in which he stated that he could not fulfil his promise of marriage to her, when, Sergeant Vaughan, for the defence, objected to the letter being put in evidence, as it was decided that no proof of breach of promise of marriage could be put against the defendant in a case of seduction.

The Lord Chief Justice declared the letter, containing evidence of a breach of promise of marriage, to be inadmissible as that might be made the subject of a separate action.

Thomas Chisholm (not Cheshunt as stated in the Annual Register), the brother of Mrs Wing, said that she had been left a widow eight years ago, with three daughters and one son. Mrs Wing moved to Cambridge, leaving Susannah and the other children under the care of their grandfather, until 1820. Susannah was now between 18 and 19 years of age and knew Jenkins, at that time an assistant to a Mr. Crisp, who visited the family professionally. Thomas Chisholm first received intimation of the pregnancy of Susannah in January, 1821, but, prior to that time, he had observed that Mr. Jenkins paid marked attentions to her. When he learned of the circumstances which had taken place, he wrote to Jenkins to come forward and give an explanation of his conduct and intentions. In answer he received two letters, appointing interviews, which, however, he did not keep. After some further correspondence, Jenkins sent a letter, which was read out in court. It stated, in effect, that he would no more make his appearance in Meldreth and that he understood that the matter, which was to have been kept secret, had been disclosed by Harriet Wing, one of the sisters. His friends had deserted him and in his unfortunate situation, he could no longer think of marrying Susannah. He would leave the area and go to the West of England. Jenkins added, that he had certainly meant to marry Susannah, for it was with honourable views that intercourse had been carried out. Chisholm stated that Susannah had been a most strictly virtuous girl before her intercourse with Jenkins.

Susannah Wing was then called. She was the wreck of a rural beauty.

She was brought into court by her brother. She appeared to be in the late stages of decline. Upon the appearance of so deplorable an object there was an expression of great compassion in the court. She was the wreck of a rural beauty.

Susannah stated that she had known Jenkins for more than two years and that she had been living with her mother when she had first became acquainted with him. He used to call very frequently to attend her brother and that it was during this time that she herself was unwell and so Jenkins also attended her. It was in the winter, when her mother was at Cambridge, that he came to attend her in the bed-room to which she was confined. He had become acquainted to her for some months before this and said that he wished to ‘pay his attentions to her’. On one particular occasion, whilst she was confined to her bed, he accomplished his wishes. The intercourse went on from time to time afterwards against her wishes, as he told her that if she did not submit he would never marry her but, if she did, then he certainly would. The child, born in May last, was the consequence of their intercourse. Jenkins continued to visit her after that period.

Susannah, on her cross-examination by Sergeant Vaughan, positively swore that she never had any intimacy with any other man before Jenkins. Her brother surprised them on the first occasion but she begged him not to tell their mother as Jenkins wanted it to be kept a secret from her. It was not until after the baby was born, that her mother was informed of it. Jenkins continued to visit her with the knowledge of her brother but was not allowed to attend her in her bedroom alone.

Sergeant Vaughan put it to Susannah that she had had improper intercourse with gentlemen named as John Course, Thomas Hawkes, and William Pennington. Susannah said that she had only known them as visitors at her mother’s house.

Sergeant Vaughan then called Thomas Hawkes of Meldreth. He remembered seeing John Course at Mr Wing’s house at about 3pm four or five years before, when he went there to meet a friend. He tried to get in, but found the door locked. He looked in the kitchen window and saw John Course with Susannah Sophia Wing sitting on his knee with her arms round his neck. Thomas Hawkes added that John Course left the house by the back door and ran away. He never told any of the Wing family what he had seen.

John Course said that he had known Susannah from infancy and was in the habit of visiting the public-house. Susannah was in the habit of calling very frequently at his house to see his sister. He swore that he had had criminal intercourse with her 3 or 4 years ago and that she was always the first to make advances. He swore that on the particular occasion spoken of by Thomas Hawke that he was indeed in the situation described. He had never promised to marry her, nor had she ever asked him to do such a thing. He could not avoid her and he continued his meetings with her until he was married himself.

Course, examined by Sergeant Lens, said that the interval, during which the connection was carried on, was about two months. He was married about a year since and he now carries on business at Meldreth.

William Course, the brother to the John, swore that Susannah used to visit them at their house, which was about half a mile from the public house. She used to stay until after dark when she was afraid, or said she was afraid and William used to accompany her home. On one Sunday evening he went to the public house, when Susannah was alone in the house and that he took with her what liberties he pleased.

William Pennington was also called and swore that Susannah and he had been upon the most intimate terms.

The Lord Chief Justice stated to the jury that there had been no evidence whatever of connivance upon the part of Mrs Wing who had sustained from Jenkins one of the deepest injuries. He asked them, whether they could believe one word from the mouths of the fellows who had come forward for Jenkins with such wicked haste to publish their own shame. He recommended that damages should be given such as would not go the whole length of ruining the defendant.

The jury asked a question with regard to the property of the defendant. The Lord Chief Justice said that no evidence had been given to prove that he had any.

The verdict was found in favour of Mrs Wing for the plaintiff — Damages £150.

The original transcript of the case can be read by clicking here. Several newspaper reports of the case can be viewed by following the download links below.

Postscript

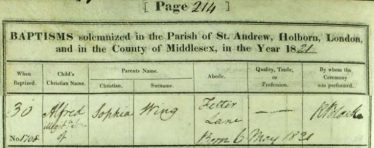

Susannah was obviously in poor health at the time of the court case and she died not long afterwards. Her burial is recorded in Cambridge St. Edward on 3 July 1822. She was 19 years old. Her address was given as Maid’s Causeway, Parish of the Holy Trinity. Her death may explain why her son, Alfred, referred to himself as Alfred Augustus Paul Jenkins Wing throughout his life. He may have been quite close to his father despite his new family in Melbourn and his old indiscretion. Alfred went on to become a schoolmaster and an accountant, possibly funded by the £150 damages awarded. Another page on this website gives more detail on the family history of the Wing family.

We are indebted to Trevor Hamilton for providing additional information for this page.

Comments about this page

Thank you very much for adding such an interesting comment, Trevor. In the light of your comment it would appear that this story must be about Sophia Wing, not Gwynne. Gwynne is the name given in The Annual Register (where we first came across the story). However, we know of no Gwynnes in Meldreth. Wing would certainly “fit” better: the parish register shows that a Susanna Sophy Wing was born in Meldreth on 21 June 1803 and baptised on 10 February 1805. This ties in with the age of Susannah Sophia Gwynne in the story above. In addition, we know that a William Wing was granted a licence to run the Green Man public house in 1795 and from 1764 to 1837, a James Wing was landlord of the Bell Public House. Quite how “Wing” became “Gwynne” is a mystery. They may sound reasonably similar when spoken in the local Cambridgeshire accent or, spelled phonetically, “Gwin” is an anagram of Wing. If you are able to provide us with the court article from the newspaper we would be very grateful.

This story is the exact scenario that I have been searching for in my family tree, except that I am looking for a young Sophia Wing who was improperly attended to by surgeon Augustus Paul Jenkins from Melbourn. She gave birth to Alfred (Augustus Paul Jenkins) Wing in May 1821 in London. So I am looking for a link between the Gwynnes in Meldreth and the Wing family (there is a court article in a British newspaper which describes the same case but is headed Wing v Jenkins)

Add a comment about this page